Imagine this: you are an educator who teaches a large class and would like to give your students the opportunity to practice as much as they like. So you create questions. But that is cumbersome. Instead, you’d like (or: I’d like) an automatic pipeline that takes in the material you teach and spits out useful, and automatically generated questions. Ideally: an infinite number of high-quality formative assessment questions on different difficulty levels.

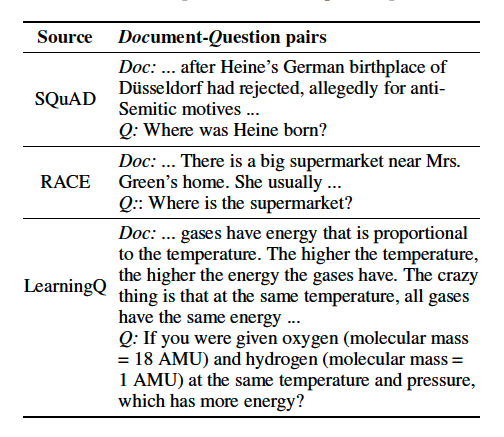

Question generation research makes this possible. The problem of current question generation works though is that they are largely evaluated on datasets such as SQuAD or RACE which have either been created for machine reading comprehension or language comprehension tests - they typically contain all information to answer a question to be available in a short piece of text). This is of course not very useful for educational questions, as it covers only the lowest levels of learning. Take a look at the following document/question examples, two from SQuAD and RACE and one from our LearningQ dataset:

For human(!) learning, we are interested in questions whose answers cannot be simply read out from a piece of text available to the user. To train neural (what else these days?) question generator approaches, we thus need a dataset that contains those cognitively more difficult questions. The process of creating such a dataset is described in our ICWSM 2018 paper:

@paper{ICWSM18LearningQ,

author = {Guanliang Chen, Jie Yang, Claudia Hauff and Geert-Jan Houben},

title = {LearningQ: A Large-scale Dataset for Educational Question Generation},

conference = {International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media},

year = {2018}

}

The source code, dataset description and links to the actual dataset are available here.

Data Collection

Where do we get a very large set of useful (for learning) and diverse (covering various topics) document-question pairs from? We looked at a number of educational Web portals and eventually settled on gathering questions from TED-Ed and Khan Academy. The former contains learning materials and questions created by instructors (thus: high-quality), the latter contains learning materials (articles and videos) and questions that learners post about the materials.

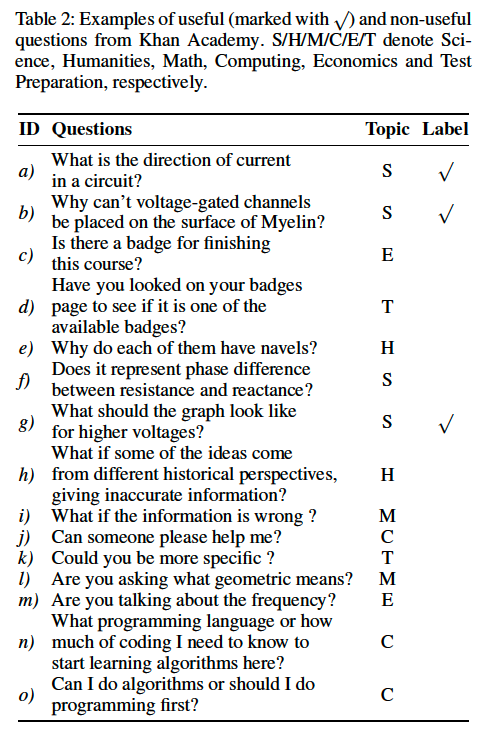

While we were able to take all 7K crawled instructor questions from TED-Ed at face value, we spent a significant amount of time and annotator effort to built a suitable classifier for the more than 1 million questions crawled from Khan Academy. In the end, our classifier identified 223K unique useful questions; below are a few examples of useful/not useful question from this source.

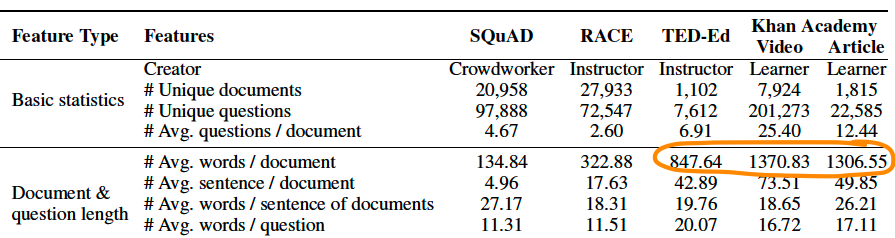

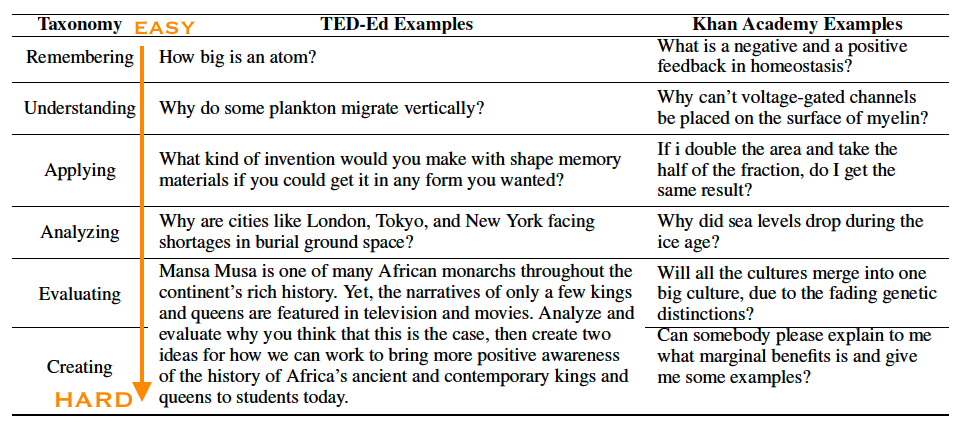

The questions in LearningQ cover a wide range of educational topics and contain long and cognitively demanding documents for which question generation requires reasoning over the relationships between sentences and paragraphs; this is in contrast to SQuAD and RACE as seen below. As a result, a significant percentage of LearningQ questions (30%) require higher-order cognitive skills to solve (such as applying, analyzing), in contrast to existing question-generation datasets that are designed mostly for the lowest cognitive skill level (i.e. remembering).

We actually find questions across all cognitive levels (we took Bloom’s taxonomy as our starting point) in our dataset:

Baselines

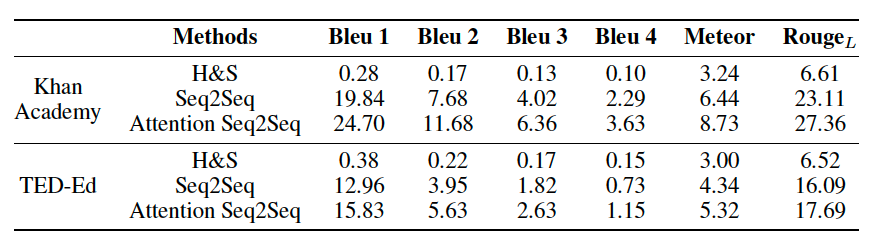

To understand the effectiveness of existing question generation methods in producing educational questions, we evaluate both rule-based and deep neural network based methods on LearningQ. Extensive experiments show that state-of-the-art methods which perform well on existing datasets cannot generate useful educational questions. The best Bleu 4 score achieved by the state-of-the-art methods (i.e., Attention Seq2Seq) on SQuAD is larger than 12, while on LearningQ it is less than 4, which indicates large space for improvement on educational question generation.

What now?

Now we get to work, trying to improve over our baselines. The vision will only be a reality when we can with reasonable confidence generate good questions (we are far away from excellent). The application domain for us are MOOCs, leading to research and prototypes with potentially tens of thousands of users.