In recent months, we spent a lot of time and effort to design and implement a well-functioning open-source collaborative search system called SearchX. I wrote about it here. Having done all the implementation work, now is the time to reap the benefits of the work, i.e. run experiments with our new and shiny research tool.

Enter Search as Learning.

The field of Search as Learning addresses questions surrounding human learning during the search process. Existing research has largely focused on observing how users with learning-oriented information needs behave and interact with search engines. What is not yet quantified is the extent to which search is a viable learning activity (and alternative) compared to instructor-designed learning. Can a search session be as effective as a lecture video — our instructor-designed learning artefact — for learning?

The answer to this question (or, at least an answer in a very specific setting) can be found in our CIKM 2018 work (PDF preprint), led by Felipe Moraes, with strong contributions from Sindunuraga Rikarno Putra, a Master student doing his thesis work in our lab:

@paper{CIKM2018SAL,

author = {Felipe Moraes, Sindunuraga Rikarno Putra and Claudia Hauff},

title = {Contrasting search as a learning activity with instructor-designed learning},

conference = {CIKM},

year = {2018}

}

(on a side-note, I don’t believe the new rating system at CIKM worked very well, papers ended up with lots of weird scores … anyway)

User study

We designed a user study that pits instructor-designed learning (short high-quality video lecture as commonly found in online learning platforms such as edX, TEDEd, Khan Academy) against different instances of search, specifically:

- single-user search;

- search as a support tool for instructor-designed learning; and

- collaborative search.

As a starting point, we went after vocabulary learning, a rather easy to evaluate learning task that also other IR researchers have used quite extensively. We used our SearchX framework to not only provide the collaborative part, but to facilitate the entire study setup as well. Here is how the setup worked:

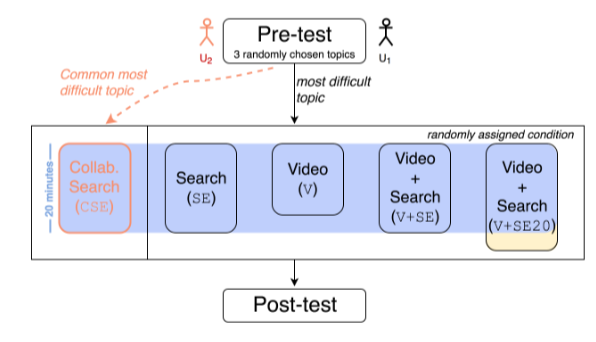

Across all five conditions, every participant (we had 151 in total and ended up using workers from the Prolific platform as CrowdFlower workers turned out to be too unreliable) first conducted a pre-test for which randomly three of the ten available topics (such as radioactive decay, urban water cycle, glycolysis) were selected. We asked our participants for each of the topics to assess their knowledge on ten vocabulary items (these items were all domain terminology, e.g. Auger electron, coagulation, krebs cycle) and assigned the participants to the topic they knew the least about. After the participants completed their condition, we evaluated their knowledge on those vocabulary items again.

As in prior works, we looked at the learning gain as a metric of learning, which is basically the difference between post-test and pre-test knowledge. A few more details on the five conditions:

- Video (V): a participant is given access to the MOOC lecture video and can watch it at her own pace (those videos are between 4 and 13 minutes long);

- Search (SE): a participant is provided with the single-user search interface and instructed to search on the assigned topic for at least 20 minutes; the search back-end was hooked to the Bing Web search API to serve high-quality Web search results;

- Video+Search (V+SE): a participant first views the video as in the video condition and afterwards is provided with the single-user search interface and asked to search on the assigned topic. The minimum time for this task (across both video watching and searching) is 20 minutes;

- Video+Search (V+SE20): similar to V+SE, but now with 20 minutes of search time;

- Collaborative Search (CSE): two participants search together using the collaborative version of SearchX for at least 20 minutes. This variant of SearchX (since this is a modular implementation we can easily switch interface features on and off) included the shared query history widget, shared bookmarking and a chat window.

The median time our participants spent in the experiment was 49 minutes; we paid out £5.00 per hour.

Vocabulary knowledge state levels

We measured the learning gains of our study participants in the vocabulary learning task across four knowledge state levels:

- I don’t remember having seen this term/phrase before.

- I have seen this term/phrase before, but I don’t think I know what it means.

- I have seen this term/phrase before, and I think it means ___

- I know this term/phrase. It means ___

These levels do not only provide us with information on how certain our participants are about their learning (state (3) vs. (4)) but also required participants to write down their idea of the definition of each term, which we then could manually check.

Results

We found that:

- lecture video watching yields up to a 24% higher learning gain than single-user search;

- collaborative search for learning does not lead to increased learning; and

- lecture video watching supported by search leads up to a 41% improvement in learning gains over instructor-designed learning without a subsequent search phase.

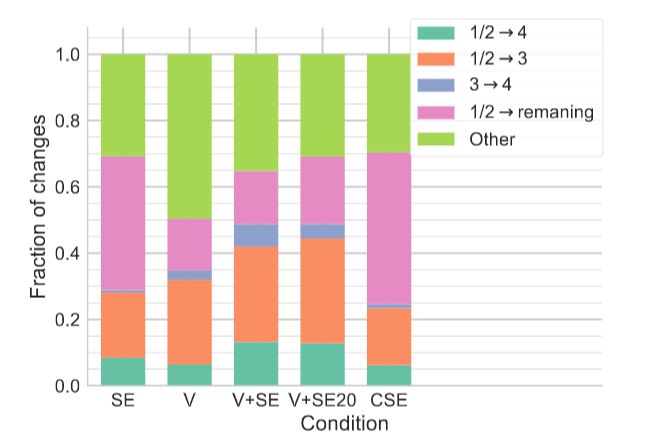

Below is an overview of the vocabulary state changes between pre-test and post-test aggregated across all topics/participants for each condition:

Here, 1/2 → 4 indicates the fraction of vocabulary state changes between the pre- and post-test that went from (almost) no knowledge to knowing the term/phrase; 1/2 → remaining indicates no changes in knowledge state between the pre- and post-test and so on.

Across all conditions, participants in SE have the largest percentage (>40%) of vocabulary items that remain unkown to them (knowledge levels 1/2). As expected in the V (+SE/SE20) conditions this percentage is considerably lower (15%-20%) as all tested vocabulary items were mentioned in the video (that’s a result of us defining the vocabulary terms). Collaborative search (CSE) did not help at all, two participants searching together gained the least knowledge; quite a deviation from our expectations. Interestingly, despite achieving the least, the collaborative search participants were the ones that self-reported the least problems in their learning!

Limitations, i.e. the road to future work

Like any user study, there are many more things that can/should be done:

- So far, we have restricted ourselves to the vocabulary learning task—an open question is whether the findings are robust across a number of cognitive skill levels.

- With increased cognitive skill levels we also need to ex- plore better sensemaking interface elements.

- The study was completed by crowd-workers, but ideally we conduct a similar study with actual MOOC learners.

- We need to explore the overhead of collaboration in the search as learning setting and design interfaces to decrease the costs of collaboration.